ICARO

In his recent work ‘Icaro’, commissioned by Stuttgart State Opera, Alexander Fahima dissects what is commonly established as an operatic staging (mimetic representation, dramatic climax, vocal parts and orchestral sound, central perspective and distanced audience position, use of stage technology, light and video design, costume and mask)

and thus poses the crucial question of the actual core of a Gesamtkunstwerk.

This core is, as shown in his previous works, always a game with expectations. In a performance venue that has dedicated itself decidedly to an audience of 12 years and older, the artistic means that Fahima deploys are quite different than in a work which appropriates Brecht’s theory of teaching plays (‘The Scandal in Baden-Baden’, Festspiele Baden-Baden, 2012) or one other that reinterprets Wagner’s idea of infinite melody as a digital live stream performance (‘On reading #foucault’s #lusagedesplaisirs feat. a very slow #bohemianrhapsodyremix [aka The Rules of Attraction, opéra concrète]’, Volksbühne Berlin, 2021). All these approaches have in common, however, that the actual performance does not manifest itself through the action on stage, but rather in the virtual space between (and including) the audience and the stage.

Fundamental to Fahima’s method is his premise that the opera employed in each case is never only shown as what it is catalogued in the opera guide. However, the expectation which can be evoked by such advertising texts is used as main material and starting point of all artistic inventions. ‘Icaro’, according to the website of the Stuttgart State Opera, is a chamber opera about so-called roofers who expose themselves to both death and freedom in the unprotected climbing of skyscrapers. Fahima uses the momentum that is triggered by this blurb to draw the attention over 60 minutes to a whole series of visual and acoustic phenomena, which are held together by only the invisible chain of a narrative that at no time comes to light.

Everything seems to be connected to this officially announced ‘content’ of the opera. The at times ridiculous text masses, which soprano and baritone have to cope with, reveal this trick quite unashamedly: with the first emergence of a sung word (the choice fell on a mighty yet meaningless 'father') it becomes clear that text never happens here to carry any scenic interpretation, but at best is an occasion 'to activate something else' (in this case: a surreal animation video dialogue between two projectors). Fahima therefore recommended during rehearsals that the words of the libretto never be taken as interpretable content but rather as a trail mix, whose partly crisp partly juicy components (vowels and consonants) in such a sense should be enjoyed by the mouths and bodies of the two singers, with the sole aim of equating eating and singing as a performative act. Words here become vehicles for completely different actions than they are normally assigned to them.

Similarly, Fahima proceeds in the choice of mask and costume. Both are usually invented in the light of interpreting a text or subject, but here, for example, the make-up of the protagonist Leon - a ’mid-twenty year old male roofer in today’s urban landscape’ - was chosen to be very flamboyant. His face, with its forehead distorted by a prosthesis, is bright red and additionally crossed by a fleshy-bluish V-shaped line, only to hide it for half an hour in darkness and behind a milky foil that flows between the stage and the audience. After 10 minutes, in which you can actually stare spellbound at this animal head, darkness falls again over the events and you search for his face in the shadows like a spectre of dreams.

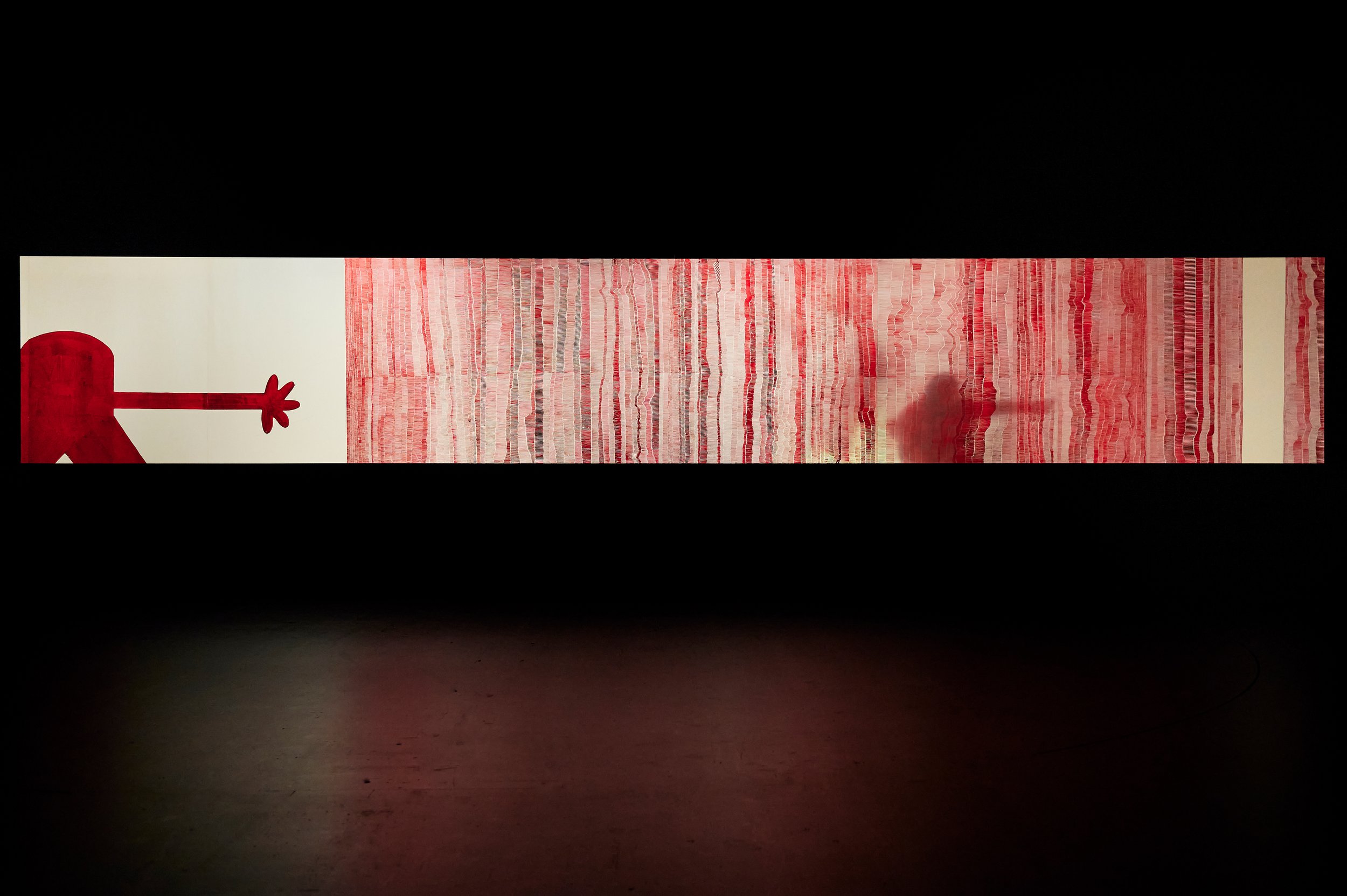

As the most important element and extension of his artistic means of not-storytelling, Fahima names the fourth wall that he has erected in front of the stage. The 38 meters of polyethylene film, which moves from left to right at a constant pace of two meters per minute, are covered with three large pictograms and 24 drawings, as well as a ten meters wide red ‘main curtain’ of 190,000 milimeter-long lines. Fahima emphasizes that apart from the pictograms which he designed as vector drawings and then transferred onto the film with thick translucent strokes, none of the other drawings were created after an actual image.

Each of these drawings started with a thoughtlessly offhand sketched line to which only parallel strokes were added. But where on the foil this started and in which density and in which direction it envolved; when this process was interrupted, changed or terminated: all this happened solely according to the decision-making power of his body, not by reason. Fahima calls this ‘the inner mushroom’, which is growing, eating, living. During the eight weeks of working on the drawings he was always aware that fortunately there would be nothing causing him to artificially connect the scenic happenings with this ‘filter’ through which they would be viewed. This connection would automatically occur, since the audience would anyway try to get hold of the stage action, so per se will have to look through the drawings at the events behind it.

Now, the actual directing for him consisted of choreographing the audience’s gaze on the 10-metre-wide stage at certain points at certain times - which in turn made use of the sophisticated lighting concept. A concept in which Fahima himself had to admit that it was more a shadow design than a light design. Here the use of prolific gaps (in the form of sudden onset of short dark phases) was not applied as a moment of irritation, but as action-structuring eye shut, which dramaturgically originates in the ingenious panning of the camera in Tarantino’s 'Reservoir Dogs' or in Lars von Trier’s idea of 'enriched darkness': the characters are about to burst into dramatic gestures and with them starts the mind game (‘Where does this lead?’) in the heads of the audience - to sink into pitch-black darkness just at the moment of revelation and leave everyone alone with their own thoughts.

In the end, Fahima’s trickery makes use of modes of both opera production and opera reception - with the aim to create an opera that never happens.

text: Eve Kendall for Foul Perfection (02/2024)

images: Matthias Baus

videos: Dana Mazur